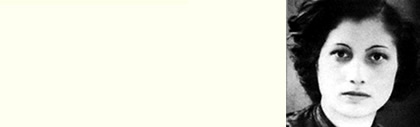

Noorunissa Inayat-Khan

1914-1944

Translated from Italian by Zubin Rota

It is – I believe – important for harpists to know the story of this wonderful woman (a student of Micheline Kahn and Henriette Renié) and I thank Bianca Bolzoni for providing us with an account of her exemplary life, written with poetic spirit and sincere admiration. This is undoubtedly the most beautiful gift that our Association could give to all our supporters. I thank Mr. Hidayat Inayat Khan, Orsola Puecher, Anne-Louise Wirgman, Shrabani Basu, Yaqin Aubert, Ameena Fumagalli, Gabriele Rota and the Nekbakht Foundation for making this publication possible. (Emanuela Degli Esposti)

Little dancers of the air

As gracious as can be

With your coloured Wings so fair,

Dance, O dance little dancers, dance,

O dance to me!

When the sun is nicely smiling on the golden

glowing hill.

When the dainty birds are singing

Butterflies,then show your skill.

When the sun is going to bed in his

night-gown red so red,

When the tiny flowers close,

Butterflies, butterflies then take repose.

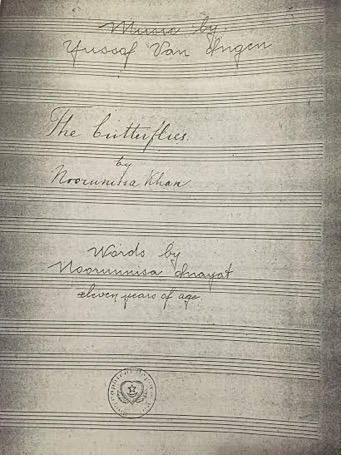

– The Butterflies, Noor Inayat Khan, 1925

Sensitive, delicate, brave: these three adjectives perfectly encapsulate the character of Noor; being faithful to immense and untarnished ideals, this Sufi Indian princess sacrificed her life to the horrors of the Second World War.

Noor-un-nisa means “light of femininity”. No brighter name could adequately express the grace and inner beauty that the eyes of this young woman disclose.

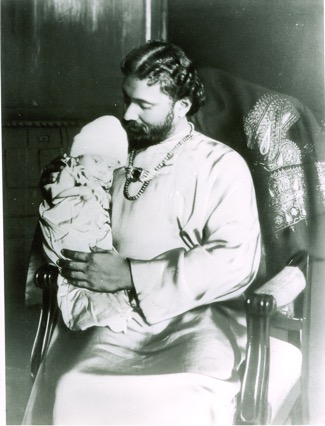

On the first day of the year 1914, Noor was born at Moscow, in a monastery not far from the Kremlin. She obtained the title of princess from her father Hazrat Inayat Khan (1882-1927), musician and Sufi Master – preacher in the West – grandnephew of Sultan Typu King of Mysore. Her mother, Ora Ray Baker (1892-1949) – Sufi name Ameena Sharda Begum – was a middle-class young woman from Albuquerque, New Mexico. At home, the tender nickname of the little firstborn daughter was “Babuli”.

In summer 1914, the incandescent political climate of pre-revolution Russia caused the Khan family to move to London, where they experienced years of financial straits. In the meantime, Noor’s beloved siblings were born: Vilayat (1916), Hidayat (1917) and Khair-un-nisa (1919).

After London came France, where the whole family settle down in 1920; but only after two years did they find what would then become their home: Fazal Manzil, the great “House of Blessing”. This house – a gift from a wealthy disciple, Fazal Mai Egeling – was located in Rue de la Tuileries, on the hill of Suresnes: the top floor window gave a vivid glimpse of the beating heart of Paris.

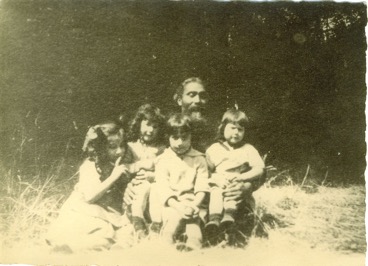

These years at the “House with a great Garden” were an unbroken string of serenity and harmony: there Inayat Khan would teach his children and his disciples the ascetic practises for interior self-perfecting (by meditation and reading); but also human solidarity, the brotherhood ideals and respect for all the religions and cultures in the world – first and foremost through music as a spiritual message. This ideal of altruism and fraternity guided Noor throughout her short existence and made her resolute in her decisions, thus leading her to a tragic and heroic fate.

Little Babuli’s artistic talent had already revealed itself at an early age: her creative output was extraordinary. She wrote many poems and stories, on which she would often compose short piano melodies for her family’s afternoon entertainment. She learnt how to read music from her brother Hidayat, writing songs with Sufi overtones in western notation; from her father she assimilated the sophisticated musical structure of ancient Indian Ragas. In these years she also wrote the lyrics of “Song to the Butterflies” (the piano accompaniment was composed by a disciple of Inayat Khan). Whenever she was moved, Noor’s crystal clear voice would become even more acute and delightful.

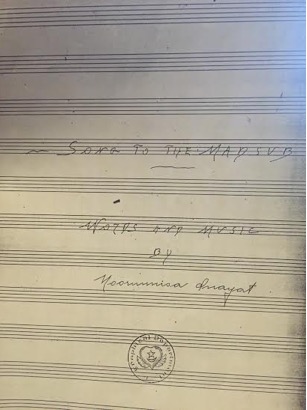

She was a cheerful and carefree young girl – barely an adolescent – when at only 13 years of age she had to cope with the grief from the death of her father – her greatest reference point. Her mother, devastated by the burden of such a severe loss, fell under the darkness of depression and distanced herself from the rest of the family; but Noor, with strong sense of responsibility, managed to take care of both the house and her siblings. The only refuge for her was writing tales for children and reading philosophical and religious books from her family’s vast book collection. Jean D’Arc (her favourite heroin) fascinated her deeply: she admired her courage and her selfless spirit. The interest for mediaeval painting drew Noor close to harp: the sight of angels playing this instrument could not be closer to her ideal of delicate femininity. She composed “Songs to the Madzub”, dedicated to her father, when she was 15 years-old.

In 1931 she decided to enrol at the École Normale de Musique at Paris, where for six years she studied harp, piano, solfeggio, analysis and harmony under the supervision of teachers of the caliber of Micheline Kahn and Nadia Boulanger. At the same time she took private lessons from Henriette Renié; during her second year she performed in a matinée at the Salle Erard, for which she was praised very warmly. In the years of the École Normale she composed “Prelude for Harp” and “Elegy for Harp and Piano”; during the summer courses she performed several concerts at Fazal Manzil: the cosmopolitan audience, made for the most part of followers of the Sufi Message, was often well-versed in music.

Every brothers had a pronunced music talent: Noor, besides harp and piano, played also the Veena, Vilayat cello and piano, Hidayat violin and piano and Khairunnisa piano.

Vilayat in particular was an estimated student of Igor Stravinsky and Maurice Eisenberg, Hidayat studied violin with Bernard Sinsheimer and conducting with Diran Alexanian while Khairunnisa, as her brothers, was a student of Nadia Boulanger.

Not satisfied with her progress as a musician, Noor enrolled for a degree in Child Psychology at the Paris-Sorbonne University: she was genuinely interested in children, and believed that university studies would help her to understand them better. The younger at Fazal Manzil regarded Noor as an exotic creature, able to recount fantastic adventures of far away places and epic Indian stories. She also wrote poetry reflecting the state of mind of her sensitive emotional sphere. She cooperated with “Le Figaro” and with several radio programmes. In 1939 (while already in England) she published her “Twenty Jataka Tales”, selected from an Indian collection of five-hundred tales portraying Buddha in his various reincarnations. In the meantime, she trained as a nurse with her sister.

As many girls of her age, Noor had dreams about a romantic marriage proposal: she fell for a young pianist, a fellow student at the music academy, but her family (faithful to their own traditions and social status) rejected their union and eventually forbade the wedding.

In this period Noor’s behaviour was shy and solitary: at the frequent meetings chaired by Vilayat she would never speak; and she would often go out for a walk in the middle of the night (sometimes – it seemed – in order to play the harp all alone).

In 1940 Hitler invaded France. The young Khans, appalled by the turn of events, decided to take refuge in London (except Hidayat, who moved with his wife and children to the South of France, not yet occupied by the Nazis), thus leaving behind what for years had been a quiet and mystical oasis – Fazal Manzil. Noor had always been taught peace and tolerance, with international horizons quite apart from any political current; she and her brother Vilayat felt that they had to concretely take part in the fight against Nazi totalitarianism and its racist abuse – indeed a fight, but without weapons. Vilayat joined the Royal Air Force, Noor the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force; in the meantime, their sister served as a nurse in several British hospitals.

The princess (brought up in a traditional culture, where women were granted little freedom and arranged marriage was still a common practice) had turned into a woman: tenacious, determined and independent. She proved herself to be especially skilled as a telegraphist; so much that she chose – after a brief training – to join the Special Operation Executive, a secret special force created by Winston Churchill for missions of sabotage behind the enemy lines in support of the resistance.

Thanks to her perfect language proficiency, she was sent to Paris undercover, in a high-risk spy mission. Under the name of Nora Baker (later Jeanne-Marie Rennier, and Madeleine as a code-name) she was put in charge of organising the partisan communication network. Noor was very talented and her commitment was flawless: she knew that any little mistake may have endangered the lives of many other people.

Eventually, the Paris spy-cell was intercepted by the German spies. All the accomplices of Noor were arrested: she was left alone, but in the hope to resume the radio operations she refused to come back to London. On 13th October 1943 she was caught after an ignoble betrayal. She went under several tough interrogatories – between psychological torture and false flattery – but she never gave any information to the GESTAPO agents.

After having attempted to escape twice – unsuccessfully – a direct order came from Berlin: to classify her as Nacht und Nebel (‘night and mist’), destined to disappear forever. In November of the same year she was brought to the Pforzheim prison, where she was kept in complete isolation – hands and feet tied together. On 12th September 1944, after months of brutal imprisonment, she was interned (together with three other agents of the French resistance) in the Dachau concentration camp. Beaten up and tortured by a SS official, she was executed – shot in the back of the head – on 13th September at dawn. She displayed no surrender or fear to the very end.

The fierce cruelty of Nazism may have violated her life, but her dignity was left intact.

Her last word was liberté (‘freedom’).

In England she was posthumously awarded the St George’s Cross, the Military Mention and the Knighthood of the Order of the British Empire; in France the War Cross. In 2012 – to the presence of Anne, Princess of England – a commemorative bust of Noor was placed in Gordon Square Garden in London.

Hidayat Inayat Khan, the only living member of Noor’s family, dedicated to his sister the moving symphonic poem “La Monotonia”, which he then performed as a conductor in several European cities. View Performance of La Monotonia.

Noor’s harp was brought back to Fazal Manzil.

[… ]“O King”, replied the monkey, “I am their chief and their guide. They lived with me in this tree, and I was their father and I loved them. I do not suffer in leaving this world for I have gained my subjects’ freedom. And if my death may be a lesson to you, then I am more than happy. It is not your sword which makes you a king; it is love alone. Forget not that your life is but little to give if in giving you secure the happiness of your people. Rule them not through power because they are your subjects; nay, rule them through love because they are your children. In this way only you shall be king. When I am no longer here forget not my words, O Brahmadatta!”

The Blessed One then closed his eyes and died. But the King and his people mourned for him and the King built for him a temple pure and white that his words might never be forgotten.

And Brahmadatta ruled with love over his people and they were happy ever after.” – Noor Inayat Khan, The Monkey-Bridge

At the end Noor's monkeys crossed the bridge, escaped from the evil king and found the street of freedom.

I wish to thank Mr. Hidayat Inayat Khan for his precious help. My warmest thanks go also to writer Orsola Puecher – for introducing me to Noor’s life and personality –, to Anne-Louise Wirgman of the Suresnes archive, to writer Shrabani Basu and to Yaqin Aubert for their gracious support, and to the Nekbakth Foundation for permission to use the images. Many thanks also to Ameena Fumagalli and Gabriele Rota for helping me with the translation.

SOURCES

Spy Princess the life of Noor Inayat Khan by Shrabani Basu, ed. The History Press, 2006.

Noor-un-nisa Inayat Khan–Madeleine by Jean Overton Fuller, ed. East-West Pubblications, 1971

Venti Storie Jakata by Noor Inayat Khan, translated by Ameena M. Grazia Fumagalli, Blurb.com, (ultima edizione 2013)

Venti Vite Del Buddha by Noor Inayat Khan, translated by Federica Alessandri, Elliot Edizioni, 2014.

Noor Inayat Khan Nemica del Reich

The Nekbakht Foundation

13 giugno 2015 - Storie. “Storia di Noor” con Giuliano Boccali, Orsola Puecher